Many entrepreneurs complain about not earning enough and being unable to calculate selling prices correctly: essentially, they don't know how to allocate costs to the product. Even accountants don't have the time or the skills necessary to set up an industrial costing system that also serves to correctly define the price lists at which to sell. Therefore, it's all too common for prices to be set based on assumptions or rough estimates.

SMEs typically lack an analytical industrial accounting system that can effectively support the entrepreneur's decision-making process by understanding production costs and the contribution margin of individual orders or product lines.

Even without the need to implement an industrial accounting system, which is very costly for a small-to-medium business, there is a simple way to determine the costs to be attributed to the product: the industrial analysis of the income statement, combined with a mapping of the organizational and production structure. The goal is to determine the specific rates and costs to be applied to the bills of materials, i.e., the "recipes" needed to produce the products (which represent each company's assets), for the subsequent determination of the selling price. The solution lies in the direct costing methodology, which assigns variable costs (raw materials and direct labor) to the product, to which all specific production costs must be added, including depreciation of "new" machinery, electricity consumption, indirect labor, consumables and maintenance, etc., which are of a fixed or semi-fixed nature.

That said, we will already be able to develop a commercial quotation template, which takes into account every aspect and single variable, to allow the entrepreneur to sell at the right price.

If we wanted to raise the bar even higher, to understand how revenue is generated and where to intervene to improve it, it would be useful to implement a MES (Manufacturing Execution System), a management software that, in addition to scheduling production and managing the warehouse, also allows us to calculate actual production quantities and times, which can be compared with the theoretical data derived from the bill of materials.

For field data collection only, as a cheaper alternative to MES, it is sufficient to have a software interface that allows you to collect quantities and production times directly from the machines.

Let's take an example where an MES or a data collection interface with machines prove useful, in the case of a company that sells stainless steel, processed to customer specifications, and would like to know the profitability of its products to correctly formulate sales prices. To this end, we can adopt different methods: determine the revenue for each job, from which to subtract the costs directly attributable to that job, or determine the revenue generated in each processing stage, from which to subtract the related production costs. Given that there are numerous jobs, the first method could involve excessive data collection work compared to the return of useful information for the decision-making process, since management control is only worthwhile if the costs of implementing it are significantly lower than the benefits achievable. Furthermore, since the sales prices of the jobs are determined based on the planned processes, the individual processing stages become the cost and revenue centers on which to base the analysis of company profitability, eliminating the need to implement cost accounting for each job. Focusing on the second method, in order to accurately evaluate To clarify the margins achieved in the various processing phases, it is necessary to determine the average hourly production costs outside of the accounting framework and to have a MES or a data collection interface with the machines, which can track the actual quantities and times of each process based on the units of measurement used, whether expressed in square meters, linear meters, millimeters of thickness or kilograms of weight. This analysis method is aimed at calculating the hourly cost for each process (cutting, finishing, etc.) and not the individual costs per job: given that the sales price lists are defined with specific units of measurement (Euro/m2, Euro/Kg, etc.), depending on the different types of finishing requested by the customer, these price lists can be compared with the relative industrial costs, determined by the processing times multiplied by the hourly production cost and dividing the result by the unit of measurement of the price list. Thanks to a one-to-one correspondence between production order and customer order, from an MTO (Make to Order, typical of jobs) perspective and not MTS (Make to Stock, typical of production in stock), it is also possible to associate each process with the reference customer, obtaining a profitability analysis not only by machine but also by customer.

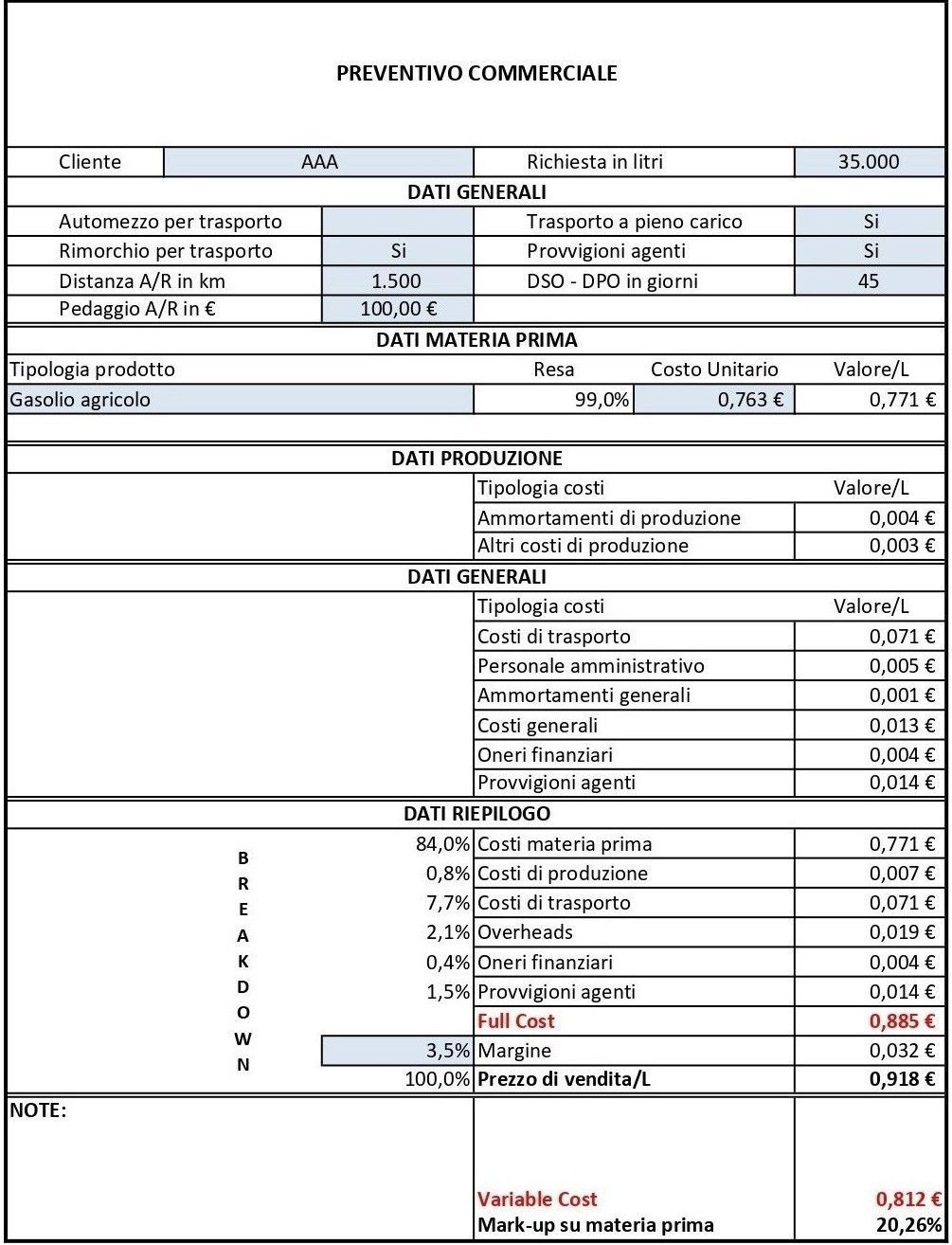

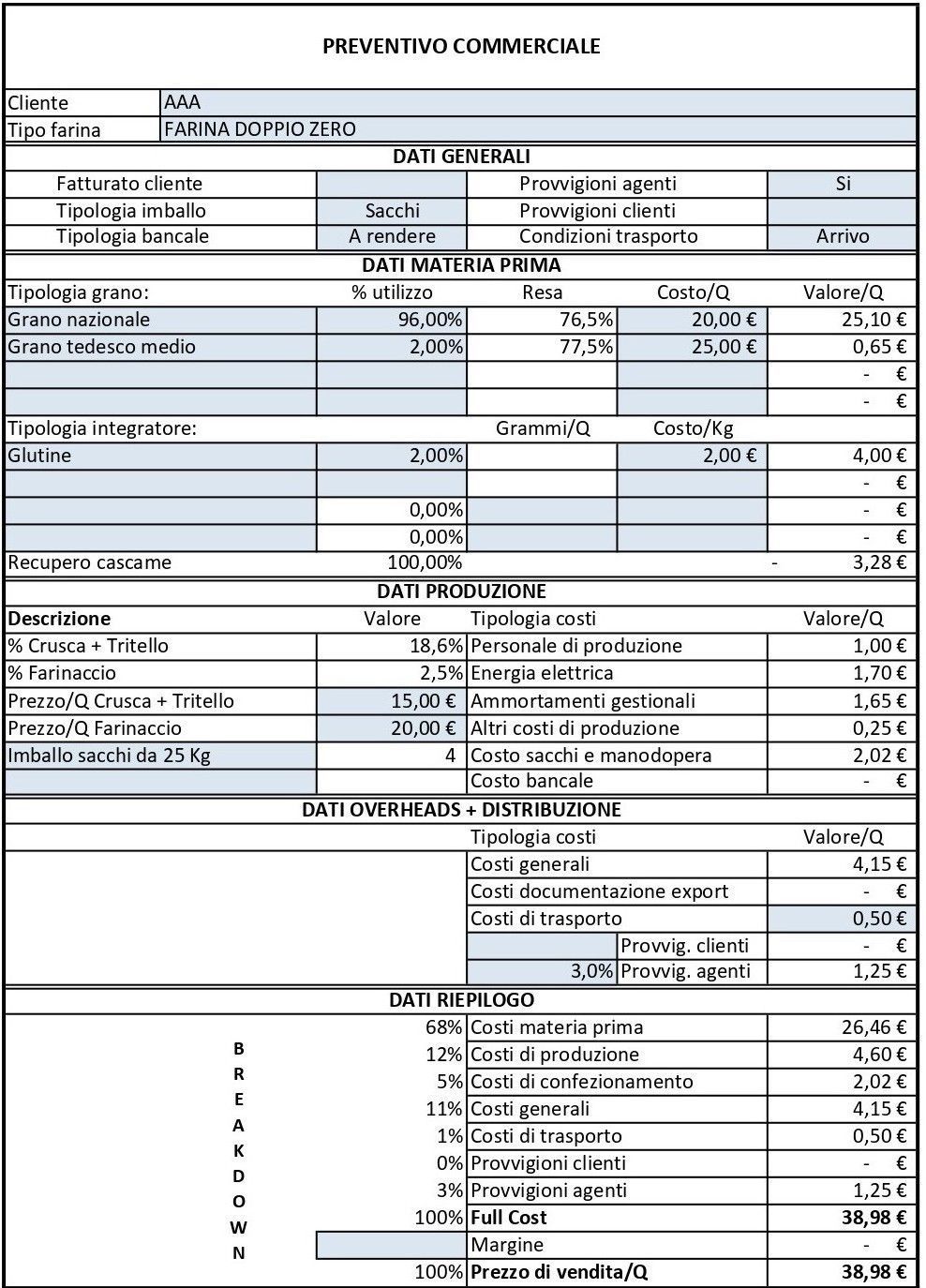

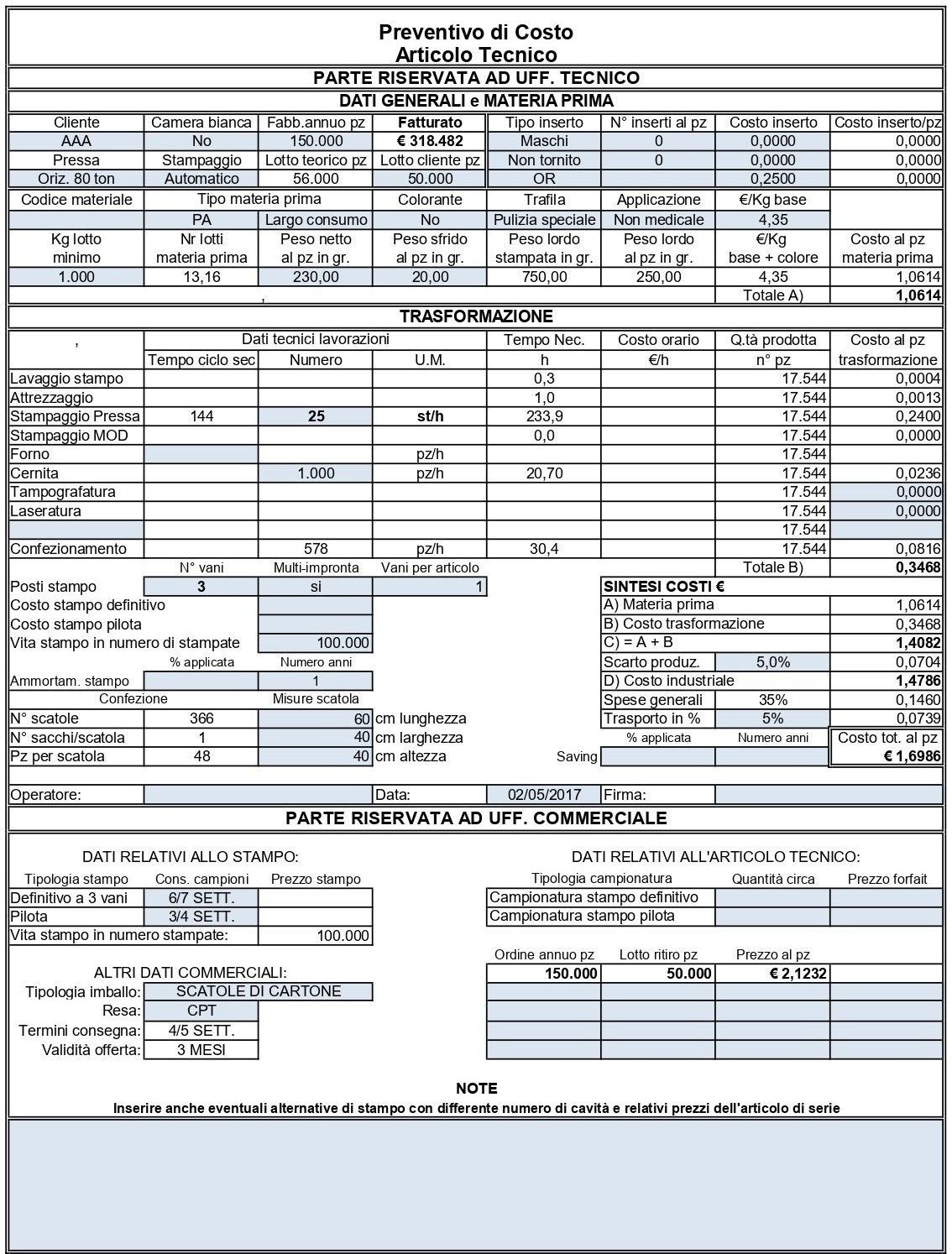

Let's now look at some concrete examples of commercial estimates we've created for companies in the following sectors: 1) the molding of technical plastic items, made to order; 2) the production of flour, based on specific customer requests or for warehouse storage; 3) the marketing of petroleum products.

1) In molding companies, the variables to consider are complex and multiple, both for the raw material (type, colorant, final application, minimum batches, inserts, scrap, etc.) and for the transformation (mold washing, tooling, press type, automatic or manual production, processing waste, oven and packaging stages, type of packaging, etc.); these variables, combined with the possibility of amortizing the cost of the mold on the product, make the estimate template extremely detailed and useful for correctly setting the selling price.

2) In the mills, the various types of purchased wheat are transformed into flours for human consumption, with different characteristics depending on the recipes used and the added supplements. This process also produces by-products (bran and bran) that are sold to the livestock sector as livestock feed. These variables, combined with the different packaging and transportation methods of the finished product, allow every aspect to be taken into account when determining the right selling price.

3) In companies that market petroleum products, the apparent simplicity of the buying and selling process, without any transformation process from raw materials to finished products, is counterbalanced by the complexity of logistics in terms of transported loads and distances traveled, which can "make the difference" between closing a transaction at a profit or at a loss: variables that the quotation model is able to calculate precisely and effectively.