Many entrepreneurs complain that they do not earn enough and that they cannot calculate sales prices correctly: in essence, they do not know how to attribute costs to the product. The accountant himself does not have the time or the necessary skills to set up a system for calculating industrial costs, which also serves to correctly define the price lists at which to sell. Therefore, it happens too often that the price is set on the basis of hypotheses or approximate estimates.

SMEs do not normally have an analytical-industrial accounting system that can effectively support the entrepreneur's decision-making process through knowledge of production costs and the contribution margin of individual orders or different product lines.

Even without the need to implement an industrial accounting system, which is very expensive for a small to medium-sized company, there is a “simple” way to know the costs to be attributed to the product: the industrial analysis of the profit and loss account, together with a mapping of the organizational and production structure. The objective is to determine the rates and specific costs to be applied to the basic bills of materials, i.e. the “recipes” needed to make the products (which represent the assets of each company), for the subsequent determination of the sales price. The solution lies in the direct costing methodology, which attributes variable costs (raw materials and direct labor) to the product, to which all specific production costs must be added, also considering depreciation of “new” machinery, electricity consumption, indirect labor, consumables and maintenance, etc., whose nature is fixed or semi-fixed.

That said, we will already be able to develop a commercial estimate model, which takes into account every aspect and single variable, to allow the entrepreneur to sell at the right price.

If we wanted to push the bar higher, to understand how income is generated and where to intervene to improve it, it would be useful to proceed with the implementation of a MES (Manufacturing Execution System), a management software that, in addition to scheduling production and managing the warehouse, also allows us to calculate the actual quantities and times of production, to be compared with the theoretical data deriving from the basic bills of materials.

For field data collection only, as a cheaper alternative to MES, it is sufficient to have a software interface that allows you to collect quantities and production times directly from the machines.

But is it possible to reduce procurement costs and develop sales without an industrial accounting system, an MES or a software interface for field data collection?

The answer is YES.

Let's take an example, starting from the definition of a fundamental quantity: the COGS, an English acronym for Cost of Goods Sold. : To simplify, the COGS represents the cost of purchasing raw materials and packaging (in industry) or goods (in trade), net of the so-called inventory delta (initial inventories minus final inventories), easily deducible from the company balance sheet. Let's suppose that the incidence of the COGS on the turnover is, for example, equal to 40%: what does this mean? This percentage represents an average and determines a watershed between products with higher and lower added value, respectively characterized by a lower and higher incidence of the COGS. Therefore, if a given bill of materials shows an incidence of the raw material lower than the aforementioned 40%, we will be faced with an overperforming product in terms of profitability and, vice versa, in the case of an incidence higher than 40%. By applying the bill of materials to sales we will have a "TAC" of the company, even without the need to implement analytical-industrial accounting, obtaining the COGS% of each product sold. We will therefore be able to push the turnover of the high added value lines, characterized by a lower incidence of the raw material and optimize purchases or outsource the production of those products with lower added value, in which the incidence of the raw material is greater than the company average. The determination of the COGS for each individual product sold also allows us to know the average profitability of each customer, with consequent analysis and optimization of the sales mix.

This approach, which focuses on the analysis of COGS, is very effective in companies characterized by a high incidence of raw materials: the other production costs will instead be monitored in their trend in absolute value or in relation to turnover.

Let's take another example, where the MES or a data collection interface with the machines prove useful, in the case of a company that sells stainless steel, worked to customer specifications, that would like to know the profitability of the products to correctly formulate the sales prices. To this end, we can adopt different methods: determine the revenues for each job, from which to subtract the costs directly attributable to the job itself, or determine the revenues achieved in each processing phase, from which to subtract the related production costs. Since the jobs are numerous, the first method could involve excessive data collection work compared to the return of useful information for the decision-making process, since management control is only worthwhile if the costs to implement it are significantly lower than the benefits that can be obtained. Furthermore, since the sales prices of the jobs are determined on the basis of the planned processes, the individual processing phases become the cost and revenue centers on which to base the analysis of the company's profitability, undermining the need to implement analytical accounting for each job. Focusing on the second method, in order to evaluate clearly the margins achieved in the various processing phases, it is necessary to determine the average hourly production costs in an extra-accounting manner and to have an MES or a data collection interface with the machines, which can track the quantities and actual times of each process based on the units of measurement used, whether they are expressed in square meters, linear meters, millimeters of thickness or kilograms of weight. This analysis method is aimed at calculating the hourly cost for each process (cutting, finishing, etc.) and not the individual costs per job: given that the sales price lists are defined with specific units of measurement (Euro/m2, Euro/Kg, etc.), depending on the different types of finishing requested by the customer, these price lists can be compared with the relative industrial costs, determined by the processing times multiplied by the hourly production cost and dividing the result by the unit of measurement of the price list. Thanks to a one-to-one correspondence between the production order and the customer's order, in an MTO (Make to Order, typical of jobs) and not MTS (Make to Stock, typical of jobs) perspective of production in stock), it is also possible to associate each process with the reference customer, obtaining a profitability analysis not only for the machine but also for the customer.

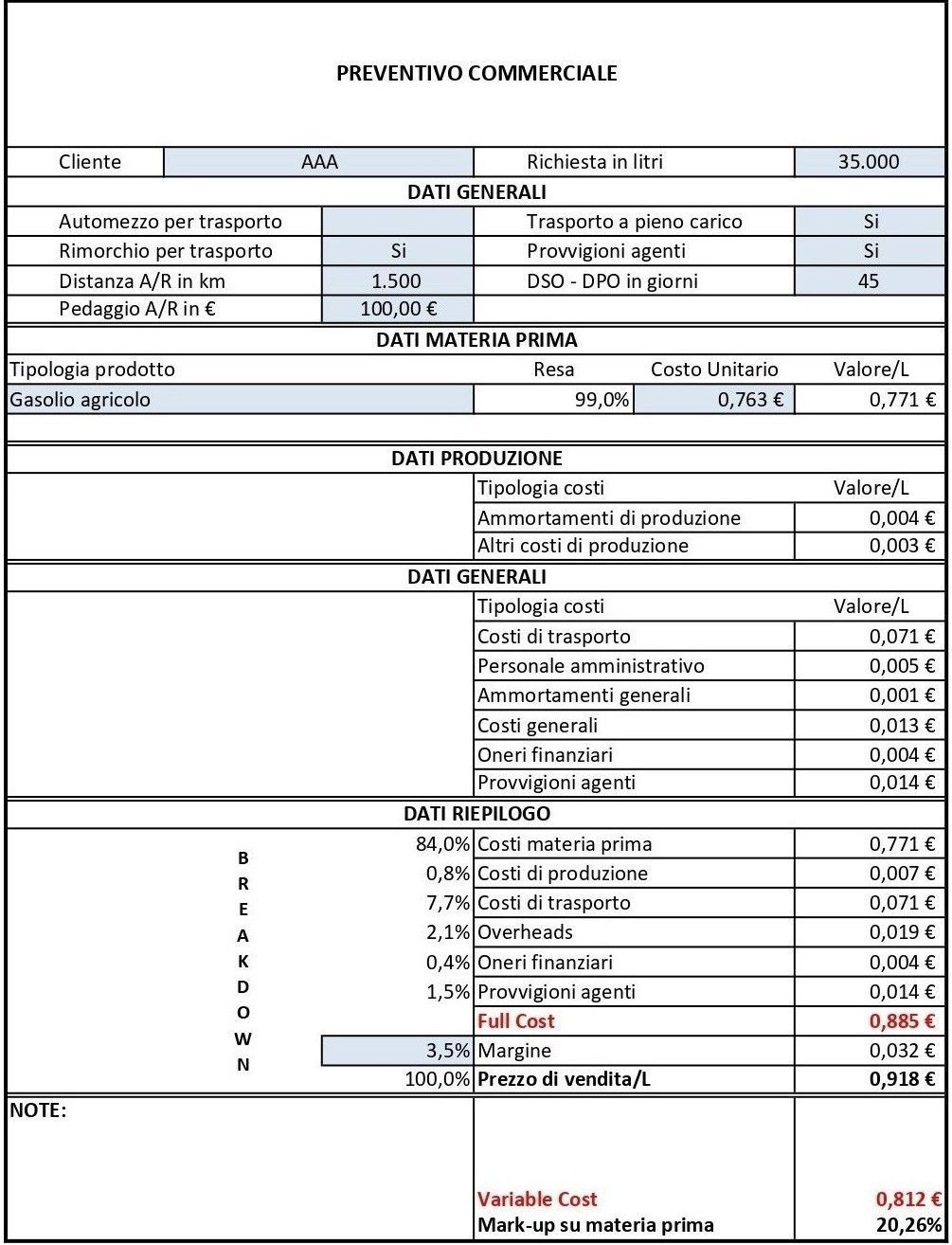

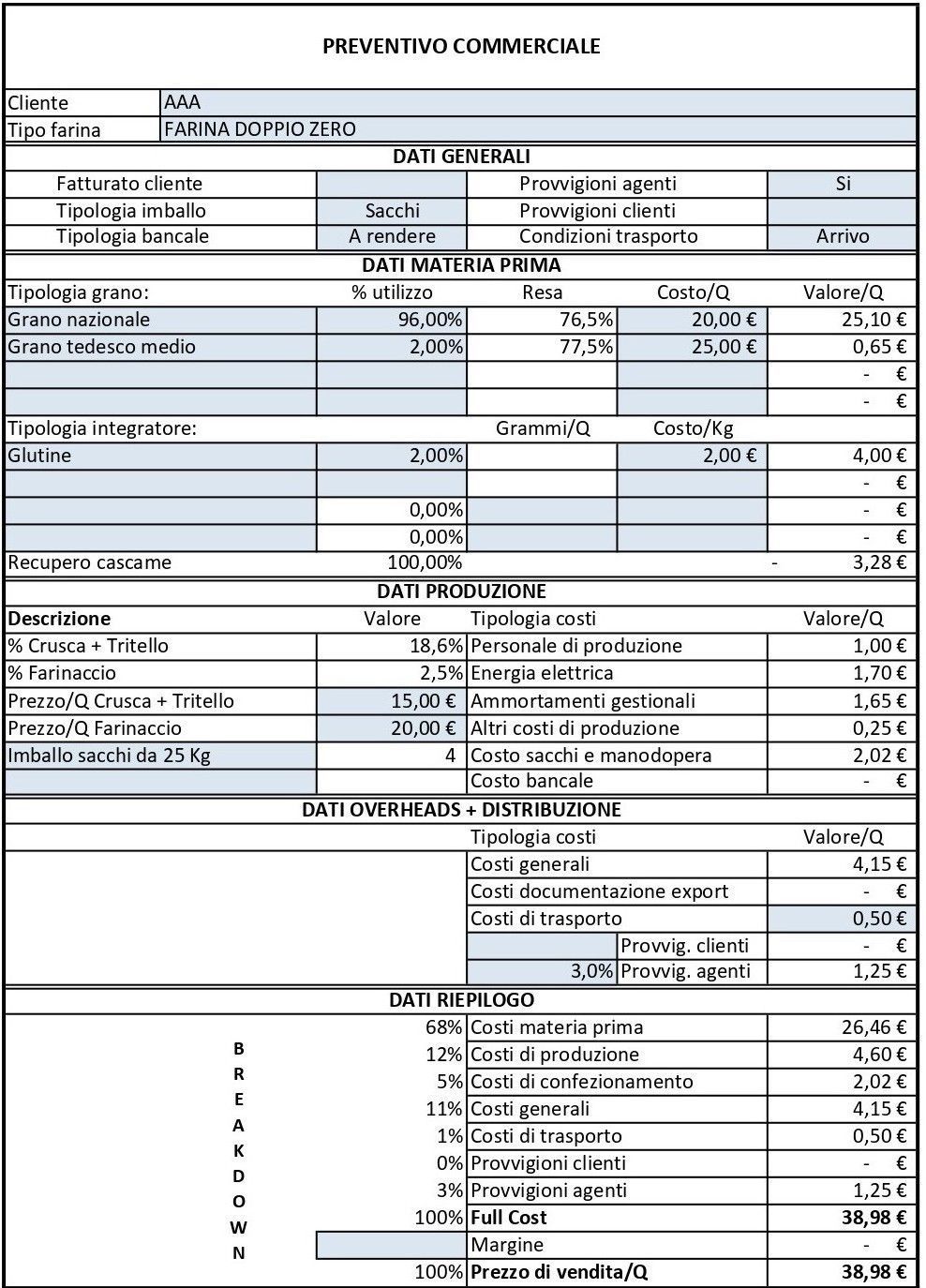

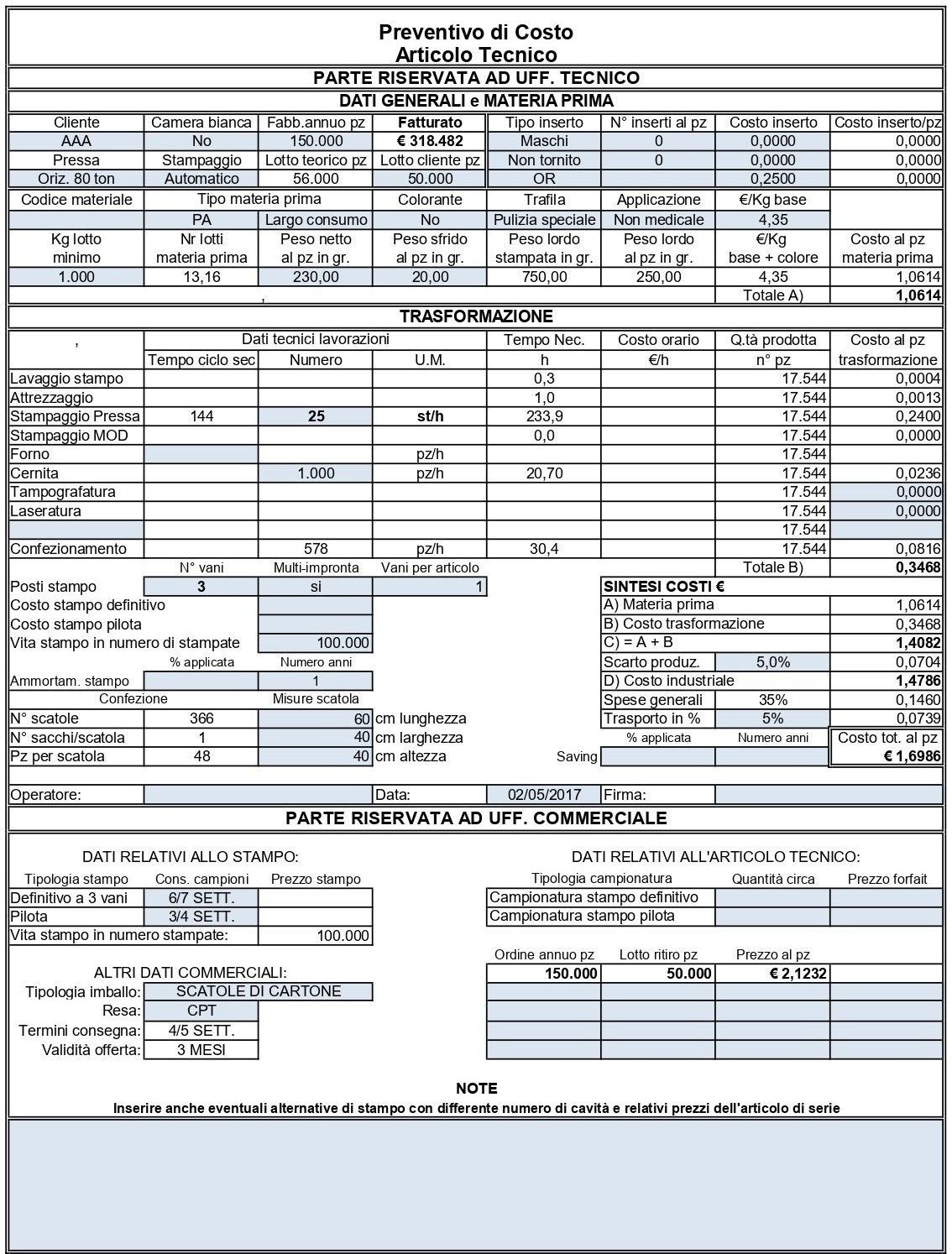

Let's now look at some concrete examples of commercial estimates, which we have created for companies in: 1) moulding of technical plastic articles, made to order; 2) production of flours, on specific request of the customer or for warehouse storage; 3) marketing of petroleum products.

1) In molding companies, the variables to be considered are complex and multiple, both for the raw material (type, colorant, final application, minimum batches, inserts, scraps etc.) and for the transformation (mold washing, tooling, type of press, automatic or manual production, processing waste, oven and packaging phases, type of packaging etc.); these variables, together with the possibility of amortizing the cost of the mold on the product, make the estimate model extremely detailed and useful for correctly forming the sales price.

2) In the mills, the different types of wheat purchased are transformed into flours for food use, with different characteristics depending on the "recipes" used and the supplements added: from this process, by-products are also obtained (bran and bran) sold to the livestock sector as feed for livestock; these variables, together with the different methods of packaging and transport of the finished product, allow every aspect to be taken into account in determining the right price at which to sell.

3) In companies that market petroleum products, the apparent simplicity of the buying and selling activity, without any process of transformation of the raw material into a finished product, is counterbalanced by the complexity of logistics in terms of loads transported and distances travelled, which can "make the difference" between closing a transaction at a profit or at a loss: variables that the estimate model is able to calculate precisely and effectively.